Hundreds of older Americans join the Peace Corps every year. David Jarmul and his wife, Champa, were among them, leaving their home in Durham, N.C., to serve for more than two years as volunteers in the small East European nation of Moldova. David worked in the local library and Champa taught English at the school.

Started by President John F. Kennedy in 1961, the Peace Corps provides technical assistance to communities in developing countries and promotes understanding between Americans and people around the world.

More than 240,000 Americans have served in 142 countries over the years, including about 7,300 volunteers and trainees now posted in 61 countries. The Peace Corps recently evacuated its volunteers worldwide because of the coronavirus outbreak but expects to restore operations after the pandemic ends.

The following article, published to coincide with National Volunteer Month in April, is excerpted from David’s new book.

Table of Contents

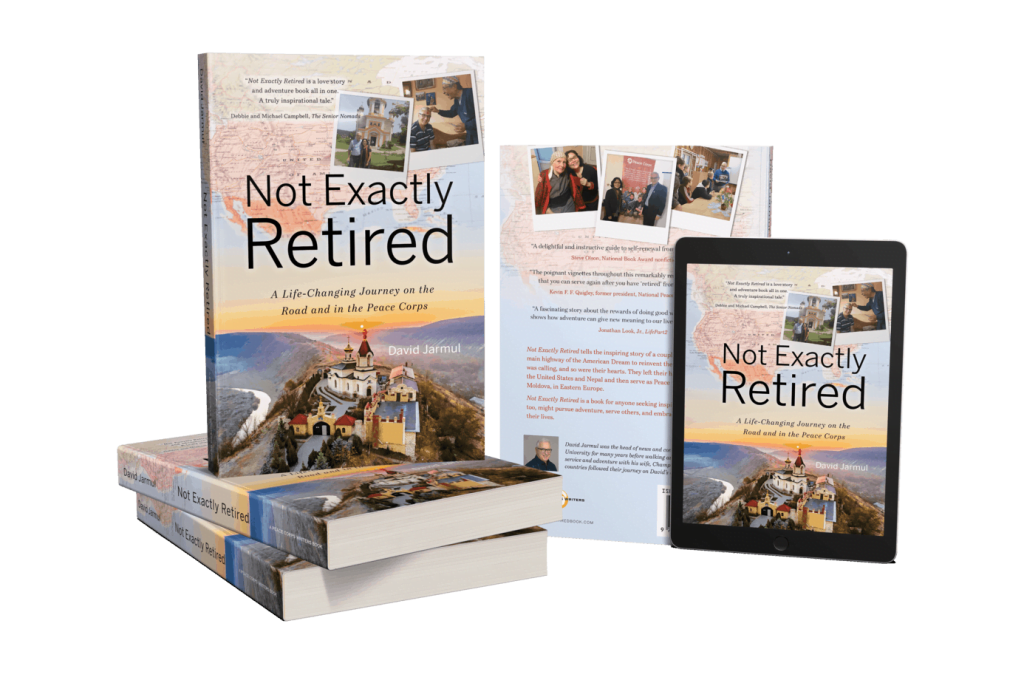

Not Exactly Retired: A Life-Changing Journey on the Road and in the Peace Corps

When Champa and I left the conventional workplace to pursue a life of adventure and service, and especially after we joined the Peace Corps, people pointed out all of the things that could go wrong.

- What if something happens to one of your children or grandchildren?

- What if you have a medical emergency?

- What if you can’t learn the language?

- What if you’re robbed?

- What if there’s a terrorist attack?

- What if things just don’t work out?

To be sure, we also heard, “That’s awesome!” And, “I’ve dreamed of that!” The cautionary questions were common, though, and they illustrated why so many people who imagine making a big change in their lives never take action. I generally responded that bad things can happen in our traditional lives, too. Since Champa and I were lucky enough to have our health, finances, and family circumstances in order, we were going to listen to our hearts and take a chance.

The Challenges

It didn’t take long after we arrived in Moldova for us to be reminded of how quickly dreams can end. During our training, an older woman in my group dropped out because of health problems and family issues back home.

One of Champa’s older friends, who had taught school for many years in the United States and other countries, also left before the end of the training. Another of her friends made it past the swearing-in process and taught successfully at her site for several months before dropping out to return to the States, where her daughter had just given birth prematurely. My best friend in my training group worked for nearly a year at his post before returning to the States for what he thought would be a quick medical procedure. He ran into complications and never made it back.

Another older man in our group returned home for several weeks to deal with back problems. He eventually returned, although he was later kicked out because he wanted to attend his daughter’s college graduation.

Still another older volunteer had a heart scare and was “medically separated” just weeks before he was scheduled to finish his service.

Some younger volunteers had medical problems, as well. Other volunteer friends returned home because they were homesick, couldn’t adjust to life in Moldova, had family responsibilities back home, or got into trouble. Several had to leave because the Peace Corps thought there were security threats in their villages. Others encountered sexual harassment, or worse.

Worldwide, more than 300 people had died since 1961 while pursuing the Peace Corps mission, many from motor vehicle accidents, but some were murdered.

The Risks Are Real

The risks were real, in other words, as we knew before we left, and as I remembered from my two bouts with pneumonia while serving decades earlier in Nepal. Yet even though Peace Corps volunteers faced special challenges, their fatality rate was the same or lower than for Americans generally when controlled for age, marital status, and educational attainment, according to one research study.

Even in a place like Moldova, where living conditions were easier than in some other Peace Corps countries, serving as a volunteer was tough. It wasn’t a vacation. The experience challenged us every day, forcing us to examine our lives and beliefs. It changed how we thought about the world and ourselves.

Every Day Was A Gift

We never regretted our decision, even when we were sweltering in airless minibusses in the summer. We viewed every day as a gift. Every time one of our friends left, especially the older ones, we reminded ourselves how lucky we were to have this experience. Something could go wrong for us, too, perhaps the next day. But so long as we had the opportunity, we were staying focused on what could go right.

The path we’d charted for ourselves was not for everyone.

Many Americans in their fifties, sixties, and seventies want to be retired in a traditional sense — playing golf, gardening, or enjoying life in some other way. Others seek to remain connected to their workplace or profession. Some end up watching too much television or getting depressed.

In a book published while we were in Moldova, Too Young to Be Old: Love, Learn, Work, and Play as You Age, sociologist Nancy K. Schlossberg described six common routes for people in the second half of life. She called them “continuers,” “adventurers,” easy gliders,” “involved spectators,” “searchers,” and “retreaters.” Champa and I fit most closely into her “adventurer” category, which she described as “an opportunity to pursue an unrealized dream or try something new.” In my case, there was also an element of “continuer,” since I’d remained active in my field of communications, although in a different way.

The Transition

I was ready for our transition, but it still took me time to adjust. I had trouble letting go of my professional identity, which I continued to highlight on my LinkedIn profile for many months. Only later did I change it to emphasize my role as a volunteer and blogger. Taking extended trips across the United States and Nepal immediately after I retired helped loosen my grip. Serving in the Peace Corps after that then provided me with a new identity and a well-established mission and structure.

Still, the whole time we were in Moldova, I knew we would eventually return home and again face the challenge of defining “who am I?” for ourselves and others. We’d need to reaffirm our identities within our families and community back home.

The Process Never Ended

Schlossberg’s book reminded me how other members of my generation had retirement dreams very different from our own, yet dreams that were equally valid and compelling. All of us entering this phase of our lives were sharing the challenge of finding a new blend of identity, relationships, and purpose to fit our circumstances.

What I came to understand during our three years away from home, especially while we were in the Peace Corps, is that the most important choice is to actually make a choice, to act instead of drift. We all face life transitions sooner or later. We can either resist them or embrace them, even as our destinations diverge.

Champa and I had a wonderful experience in Moldova.

- We felt fulfilled by our work.

- We formed great friendships.

- We learned about a part of the world we’d known nothing about and shared unforgettable moments with our local partners and fellow volunteers.

Our lives became deeper, richer, and more satisfying. We knew we’d made the right choice.

Every volunteer’s experience is different, even within the same country, and several aspects of our service made things easier for us. Most obviously, we served together, unlike most Peace Corps volunteers.

- We always had our best friend nearby to share the day’s events.

- We were also posted to Eastern Europe, specifically to a small city near Moldova’s capital, where we lived in a nice house and had access to many amenities.

- We weren’t allowed to drive, which I missed, but we did have a good internet connection and items like peanut butter and barbecue sauce in our local store.

For us, the “Peace Corps experience” didn’t include living in a hut.

Moreover, Champa and I came to Moldova with lots of experience outside the United States, so we had little trouble adjusting to a new culture. Nor were we distracted by family emergencies back home, at least until near the end when one of our granddaughters got sick. Thank goodness she recovered, but her illness was a reminder that our work could have ended suddenly. We were also fortunate to remain healthy ourselves, unlike some of our volunteer friends.

What ultimately mattered most was that Champa and I truly wanted to serve as Peace Corps volunteers and were willing to put up with sickness, separation from our family, and almost anything else thrown our way. We had a clear idea of what we were signing up for and were determined to succeed.

The Peace Corps is hard, no matter how old you are or where you serve. If you’re not fully committed, you’re probably not going to make it. We joined for many reasons, but mainly because we felt we had received lots of blessings in our lives and wanted to give back. We challenged ourselves for two years, worked hard, and felt like we made a difference. Like other volunteers before us, we also ended up feeling we received more than we gave.

I would be lying if I said we liked everything about the experience.

Overall, though, we were glad we did it. We were proud of the work we did and proud to ring the ceremonial bell on the day we finished. Champa and I didn’t change the world with our service, but we did help people while changing the path of our own lives, for the better.

Are you or someone you know thinking about joining the Peace Corps? You’ll find helpful information on the agency’s application site (www.peacecorps.gov/apply), which includes a section for older Americans. David Jarmul’s new book, Not Exactly Retired, is available online in paperback and as an e-book. The book website is notexactlyretiredbook.com.

68 responses to “Not Exactly Retired: A Life-Changing Journey on the Road and in the Peace Corps”

What a great journey. I’m sure your book will be a great success.

Thanks Sandi. I hope you and others will tell your friends about it! 😊

It’s such a great way to give back! Something a lot of people are not doing right now when others really need it! Thanks for sharing 🙂

Hi Robin, and thanks. If by “right now” you’re referring to the coronavirus outbreak, there are certainly examples of people acting irresponsibly. However, I’m focusing on the many, many Americans (and people around the world) who have been stepping forward to serve others. These include our heroic medical teams and first responders, of course, but also everyone who’s been checking on elderly neighbors or pitching in to help local families. I’m sure many “Born to Be Boomers” readers are among them.

This definitely would’ve been a wild experience to do and try.. Plus from the sounds of it very difficult and tough to do for some to make it. Thank you for sharing it 😊

Thanks, Denise. Serving in the Peace Corps can be difficult, but difficult in a good way. It’s an experience that challenges you but is certainly do-able, as nearly quarter-million Americans have demonstrated since 1961.

Y’all are gutsy! I could not do Peace Corp at my age. But I find it awesome that you did! My niece was a Peace Corp volunteer right out of college. She says it was an amazing experience.

Thanks for the comment, Dorothy. I’m glad your niece had a good experience. For me, it’s always interesting to compare notes with returned PCVs who served in other parts of the world. Our experiences were different in many ways but shared a common mission.

What a great experience! Thank you for sharing.

I’m glad you enjoyed it, Cathy.

Very interesting.

Thanks Lisa!

I never had any idea what the Peace Corp actually did, I’ve always heard of it but never knew anything about it. What a wonderful experience. thank you for sharing

Thanks Jason. My story is just one among many. Other PCVs had their own experiences, and I encourage you to check out some of those, too. A wonderful source of their first-person stories is here: https://www.peacecorps.gov/stories/.

I love the idea on this one and I put this in my bucket list.

I’m glad to hear this, April. I hope you put it in your bucket, let it marinate and then act on it!

Thank you for the insight!

Thank you, Charlotte!

Love this. I have good friends who served in the Peace Corps and it sounds like such an incredible experience.

Thanks Junell. Every Peace Corps Volunteer has a different experience, and some like it more than others, but our own experience was indeed incredible (in a good way!).

Thank you for sharing this! Peace Corps has always been a consideration for us & this gives great insight to the experience!

Hi Suzan. I’m happy to hear this. I hope my article and book give you and other readers some reassurance that joining the Peace Corps at an older age is indeed do-able, not just a crazy fantasy.

I loved reading your story! My husband and I want to retire by 50 and do more traditional traveling ourselves but have worried about missing out on any other family things. Sometimes you just have to jump and see where it takes you.

Thanks for the comment, Stephanie. My wife and I did a lot of “traditional traveling” in the years before we joined the Peace Corps, once our kids were old enough to make this possible. We became comfortable with being in other cultures and came to love the adventure of it. You never know where this might lead.

This was a fantastic read. I know many older people who have done missionary work after retirement as well as the Peace Corps.

Thanks Pauline. There are definitely some similarities between missionary work and the Peace Corps, although they are very different in other respects as well. During our service in Moldova, we lived near two Americans from Alabama who managed a home for vulnerable young women at risk for being trafficked. They did an amazing job and, in fact, are still there. Their work was grounded in their church, unlike the Peace Corps, which is strictly nonreligious. However, I felt like we were all working towards a common goal.

What a great experience and such a way to give back to others.

Thank you, Tiffany!

What a great story. Congratulations to the both of you for doing this. Thanks for sharing.

Thanks Beth. By the way, I see from your picture that you’re a tea lover. So are most of the people in Moldova, where we served in the Peace Corps. Maybe you should visit there sometime. (They have great wine, too. 😊)

Good for you, your peace corp experience sounds awesome! Maybe someday I’ll do the same!

Thanks Lora. I hope you will make this dream a reality before too long!

Thank you for sharing. It is good that you went out on a adventure.

Thanks Jody. I hope you will find a great adventure for yourself as well.

Wow! What an inspiring experience! Thank you for sharing. My niece has contemplated this as well. I believe she will someday.

You have a smart niece, Kendra!

What an amazing and inspirational journey. Thank you for sharing.

Thanks Cindy. I’m glad you enjoyed it.

God bless you that you do whatever you do! It is truly amazing. And defiantly not an easy thing for everyone. I am originally from Belarus which is very close to Moldova. And I can definitely understand the challenge of adjusting to a different life (for me it was the opposite adjustment 15 years ago when I came to the states). Lots of self-realization for sure. Lots of questions over and over again of who you really are.

I wish you the best on this journey! Best of luck! You are doing amazing things!

Thanks Anna. Wow, what an unexpected pleasure to receive a message from someone originally from Belarus. My wife and I traveled to many countries near Moldova during our Peace Corps service: Bulgaria, Romania, Ukraine, Armenia and Georgia. That was one of the nicest benefits of being posted there. However, we never made it to Belarus. Next time!

This is such an important and valuable article <3 thank you so much for shedding some light for people who don't readily know about the Peace Corps.

Thank you! Or as we said in Moldova: Cu placere (with pleasure)!

What a beautiful story. It is amazing that you have so much to give to the world!

Why amazing, Christina? Peace Corps Volunteers are Americans just like most of the readers of “Born to Be Boomers.” My own group included Americans of all ages, from across the country, single, married, gay, straight, ethnically diverse. In other words, we represented America. As we see across our country every day, and especially now during a health crisis, it’s an American tradition to serve others. When we do so, we enhance our own lives..

Wow! I love reading about this experience and how you considered this later in life. There are so many 60-somethings I know who would never consider this & being an adventurer myself, you have really inspired me! Good for you. The challenges are real, however so are the opportunities and chance for learning and growth.

Thanks Tara. It makes me happy to read this. You’re right that the challenges are real. A lot of things can go wrong along the way — a health problem, family crises back home, something unexpected like the current coronavirus outbreak that caused the Peace Corps to temporarily evacuate all of its volunteers worldwide. There’s a reason they used to call it “the toughest job you’ll ever love.” But most volunteers do complete their service successfully, and they often come home as wiser, deeper and more worldly people.

This sounds like an amazing experience, and I never really thought that the Peace Corps could be a second calling or for those who are retired.

You’re not alone, Jordan. A lot of Americans are surprised to learn the Peace Corps still exists, much less that it includes older volunteers. That’s a shame because it’s an experience that can change your life, for the better.

This is so great. I am often reminded how it is the job of the older generation to turn around and help the next one along. what a great example of that. i’m nearing that time and am hoping to transition to that with grace

A great comment, Jen. One of the best surprises we had as older volunteers was the friendships we formed with our younger colleagues, many of whom were younger than our two sons. We were all doing this together, regardless of our ages. In my book, I talk about the amusing ways in which this sometimes played out. (Example: I was sitting in the Peace Corps lounge when a Carole King song started playing. One of the younger volunteers said: “Oh, it’s that song from ‘The Gilmore Girls’!”)

This is a great post! I like the thought of being blessed and giving back.

Thanks Lisa. My wife and I decided to join the Peace Corps Volunteers largely because we felt we’d received many blessings in our American lives and wanted to give back. We ended up feeling like we did touch some lives but the ones touched most were our own.

What an amazing journey that must have been for them. My friend was in the peace corps and she met her husband and has lifelong friends from it.

Thanks Jill. Our journey WAS amazing, and life-changing, as I say in the title of my book about our great adventure. The book also describes how I met my wife during my first tour as a volunteer, nearly four decades earlier, when I served in Nepal. She and I served together in Moldova. Of course, only some lucky Peace Corps Volunteers find their spouses while serving but almost all of us make lifelong friends, just like your friend did.

I have so much respect for anyone who joins the Peace Corps. It is such a brave and selfless act.

Thanks Lora. The truth is that many of us who served in the Peace Corps, of all ages, come home feeling like we got more than we gave.

This was so interesting. Thanks for sharing and thanks for serving!

Thanks Debbie. By the way, my assigned online “mentor” before I began my service in Moldova was an older volunteer in the previous group, also a Debbie, who had been an attorney in Cleveland. So, I’ll say thanks from her, too.

What a great read! I really did not know much about the Peace Corps. I quite enjoyed reading about your experience.

Thanks for the generous comment, Casandra. If you enjoyed the article, you might also enjoy the book. (Yes, the “not exactly retired” author is being not exactly shameless 😊 in mentioning that it’s for sale online.)

Wow! It takes special kind of people to join and continue the Peace Corp mission. I am not sure I could make it through to the end. Thank you for sharing your experiences.

Thanks for the comment, Judean. One of the things I loved most about being a Peace Corps Volunteer is how it challenged me and made me stretch as a person to accomplish something important. Others felt the same way.

What an amazing thing you’ve done! Not many are cut out to be in the Peace Corp. Thank you for sharing this insight.

Thanks for the kind words, Diane, but I need to disagree with your saying “not many are cut out” to serve in the Peace Corps. A quarter-million Americans have served since President Kennedy started the Peace Corps in 1961. Thousands of them have been older volunteers, like my wife and me. Even if it’s not for you, I hope you will find something amazing to pursue in your own life.

That would be a different experience.

Different and potentially life-changing, or at least it was for me.

I have always had volunteering with the Peace Corps on my bucket list. I have friends and family who have done it, and as a teacher, I have had a few volunteers as pen pals, sharing with my students from Namibia, Indonesia and Albania.

Charlene, some of the best older Peace Corps Volunteers in our group were teachers, like yourself. I encourage you to consider the idea seriously for yourself as well. (Maybe it’s time to “kick the bucket”? 😊)